Karl Lueger

Karl Lueger

Karl Lueger

Karl Lueger

Karl Lueger

Karl Lueger

Karl Lueger was born in Vienna in 1844 and, having completed his studies, he initially practiced as a lawyer before dedicating himself to a political career in 1875. Over the years Lueger was a Member of Parliament and a member of the Lower Austrian Provincial Legislature though the core of his political activity was taken up by Viennese municipal politics. He was a member of the Vienna City Council for over 30 years and mayor of the city from 1897 till his death in 1910.

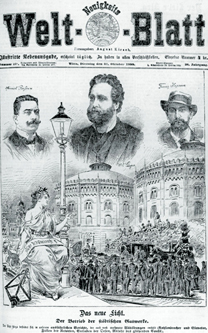

Lueger, who at first tended towards liberalism, founded the Christian Socialist Party in 1893. The party regarded itself as serving the interests of the lower middle classes and attempted to address their needs and fears during a period of rapid social change by using slogans that were anti-capitalist, anti-liberal and explicitly anti-Semitic. In order to capture the votes of these social classes a new kind of politician came into being at all levels of politics. He was the “tribunus plebes” and could be characterized as someone who entered into direct contact with the people in pubs, beer halls and market places, who tried to speak “the language of the people” and was no longer an unapproachable representative of the ruling class.

Karl Lueger was an outstanding example of this new kind of politician: he attempted to get a feeling for the mood of “the people”; he like to hold speeches in dialect, took account of the intellectual level of his listeners, made complex issues simple and tried to entertain his public with humorous remarks. He was especially successful when he attacked the supposed enemies of his listeners. He stoked antipathy to politicians with different points of view as well as national and religious minorities. His polemical attacks, sometimes extremely drastically formulated, were not directed towards reason but consciously appealed to emotions and instincts. Thus he understood how to use rousing speeches to win over the Viennese population to his cause, consciously invoking stereotypical images of alleged enemies and, in particular, making use of anti-Semitic prejudice. Every set back was reduced to a simple formula: “The Jews are to blame” and stirred up hatred with statements such as: “ We will prevent the oppression of Christians and a new Palestine replacing the ancient Austrian empire of Christians”. In the process he activated the traditional Catholic anti-Semitism directed against “the people who killed God”. He combined it with anti-liberal and anti-capitalist elements and thus addressed the widespread prejudice against “money and stock market Jews”, “press Jews”, “ink Jews”, i.e. Jewish intellectuals and businessmen. Under his leadership the Christian Socialists regarded their main political task as the reduction of the “rapidly growing power of the Jews” and the reversal of their emancipation which had only taken place in 1867.

Around 1900 the accusations of ritual murder, a relict of the Middle Ages, were once again revived. Catholic clergymen were prominent in disseminating many blood-curdling tales. Lueger was convinced that the Catholic Church was “protection and shield against Jewish oppression” and would “liberate Christian people from the shameful shackles of servitude to the Jews”. Lueger’s championing of the man in the street’s interests, his skill as a political speech-maker as well as his ambitious programme of reforms led to his party gaining the majority in the 1895 municipal elections. Lueger was elected to the office of mayor but Emperor Franz Joseph refused his consent because he considered that, in the light of Lueger’s outspoken anti-Semitism, his confirmation would undermine the laws guaranteeing equality to all citizens. As a result the elections had to be repeated four times before the monarch finally confirmed Lueger in the office of Mayor of Vienna.

During his period of office as mayor of Vienna he realised numerous large-scale projects such as the building of the second Vienna mountain spring water pipeline, the municipalisation of the gas and electricity supply, the tramway system and the building of welfare institutions such as the almshouse in Lainz and the Steinhof psychiatric hospital. In addition to the problems that derived from the rapid social changes and the end of the 19th century, Lueger’s term as Mayor of Vienna was particularly influenced by national conflicts inside the Danube monarchy. Besides that there were increases in unemployment and a wave of price increases so that people became increasingly receptive to radical nationalist slogans.

Lueger’s oft-repeated principle was: “Vienna is German and must remain German”. The vernacular, which, in the multiethnic state, was defined by nationality, formed the starting point for his political position: There was an energetic insistence that those Viennese who spoke no German be forced to communicate in that language.

Lueger also instigated changes in the Vienna naturalisation laws of 1890. The provisions stated that anyone who wished to become a citizen of Vienna had to have a spotless police and business record, have a fixed abode in Vienna for ten years and be able to prove that they had paid their taxes for the same length of time. They had to be economically self-supporting and swear an oath to the mayor “that they would fulfill all the duties of a citizen as laid out in the municipal laws and, to the best of their knowledge and abilities, they would work towards the well-being of the municipality”. An addition was made to this passage in the oath: “and to do everything in their power to uphold the German character of the city”. Furthermore, the ceremony of taking the citizen’s oath in the City Hall was bound up with a formal declaration of the principle that Vienna was a German city.

Even today one can occasionally hear statements to the effect that although Lueger did utter Anti-Semitic slogans, he didn’t mean them seriously. With his much quoted aphorism “I decide who is a Jew!” he arrogated to himself the freedom to make exceptions. This was all harmless compared to the concurrent political activity of Georg Ritter von Schönerer who represented a form of anti-Semitism based on the construct of “race”.

This ignores the fact that Lueger was the first politician to make anti-Semitism “socially acceptable” and who used it to forge a conventional political movement. Thereafter anti-Semitism appeared to many people to be both normal and respectable and it soon found its way into the political programmes of other parties. After Lueger’s death, anti-Semitism became a significant factor in Austrian political life and it was to remain so in the coming decades.

In 1926 a statue was erected to Lueger’s memory. It was designed was by Josef Müller who emerged victorious from a competition in 1912. Due to the First World War and the general lack of funding and materials, the actual building had been postponed. In 1922, the 25th anniversary of Lueger’s conformation as Mayor of Vienna, the Christian Socialist municipal party organisation revived and forced through the planned construction. In September of 1926 the re-designed square with its new monument was officially re-opened to the public.

References Andics, Hellmut: Ringstraßenwelt, Wien 1983 Geehr, Richard: Karl Lueger- Mayor of Fin de Siècle Vienna, Detroit 1990, Hamann, Brigitte: Hitlers Wien, Lehrjahre eines Diktators. München 1998 (8. Auflage), Hawlik, Johannes: Karl Lueger und seine Zeit. Wien, München 1985 Kuppe, Rudolf: Festschrift zu der am Sonntag, den 19. September 1926 stattfindenden Enthüllung des Dr. Karl Lueger-Denkmales, Wien 1926, Reichhold, Ludwig: Karl Lueger, Wien 1989, Schnee, Heinrich: Karl Lueger, Leben und Wirken eines großen Deutschen, Paderborn 1936, Spitzer, Rudolf: Des Bürgermeisters Lumpen und Steuerträger, Wien 1988